Table of contents

- Introduction

- Motivation

- THE Grid world

- Infinity

- Going 3D

- The WORLD tile

- The datastructure

- Results

- Conclusions

- Questions

Introduction

One of my passions is gaming, with electronic gaming (video games) and board games being on top of the gaming class. From a long time I have spend days drafting about game engines, game design and game programming.

These days are long gone, and now I have started a personal project to write a real game (besides all those pongs, move the character over map, and text games that I created learning new gaming libraries and programing).

When talking about game genders action adventures with nice decision choices are my top choice. I enjoy walk through new worlds and see what is hidding in the next corner. What are the sick ideas in the mind of the designers.

Most things that are written here are still draft and are just an idea. No real implementations yet.

Motivation

When walking in a world few things are worse than loading screens, we can accept a loadscreen while starting the game or teleporting to a distant locations (the teleport itself can be disguised in a load screen), but load screens to open a door house or move further throught a bridge is unaceptable. Many great games did that, but they would be better without it.

How can we create a huge game world (by huge I mean at least 100 sq. kilometers wide) and access it without loading, or at least with non noticiable load.

The main concerns here are about time to access the data, it must be done faster than user moves along the map, that would be simply solved if we load all map in memory, but that brings a second issue: memory limit, how can we load a map that is bigger than memory itself?

A grid world

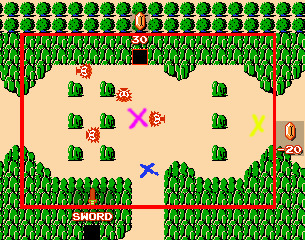

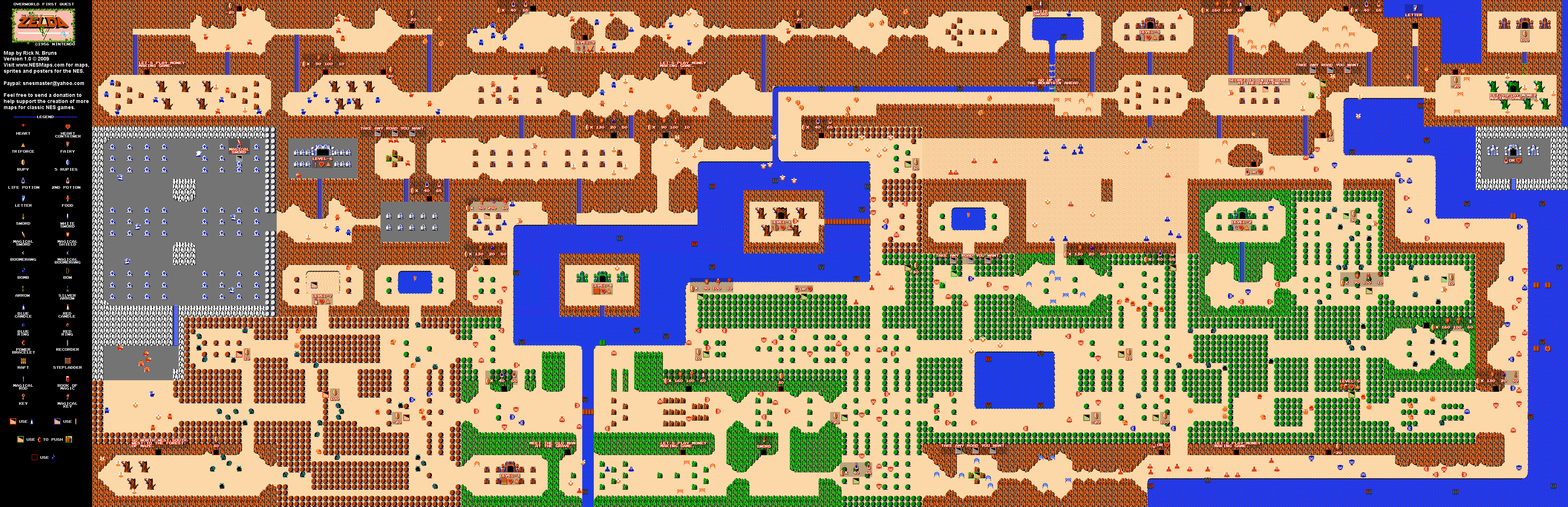

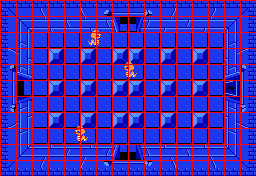

For sake of example lets take a classical game as Nintendo’s The Legend of Zelda,

.

In this game the player, represented by the green hooded character Link, always see a single area as the picture above. No matter where on the screen the player is, no matter if Link is in the center, near any of the bushes or screen boundaries. It always see the same screen, as we have shown as example in the figure 2.

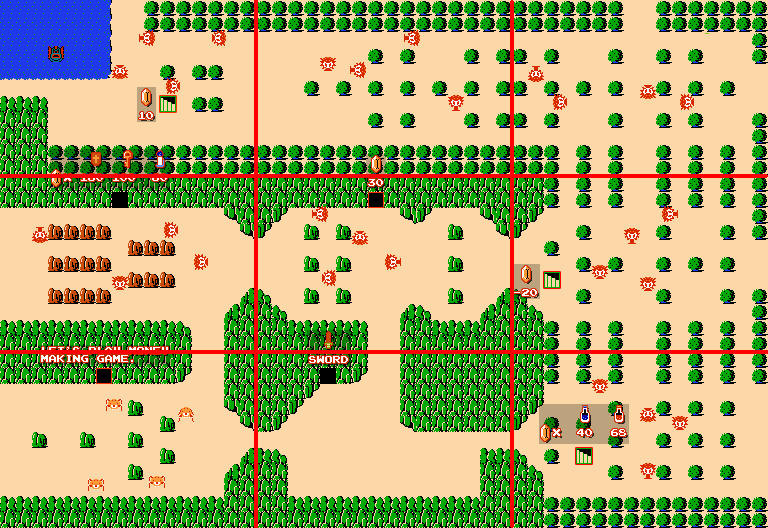

When the player touches one of the screen boundaries (in this case the top boundary isn’t reacheable because there are green mountains on the way), the game makes a transition to that direction removing the actual map from memory and loading the new map. In figure 3, I show the map around our initial map.

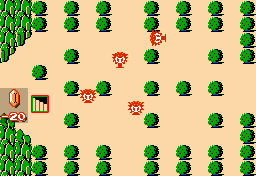

For sake of example, if Link touches the right boundary it will be presented to another screen, in this case the right screen shown in figure 4

Internally, the game drops all information about the previous map and load with the information about the new map. It does that for sake of memory limitation. The map is stored in a memory array as loosely represented here in C language.

int map[16][11] = {

{ 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2 },

{ 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 7, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2 },

{ 2, 3, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 5, 3, 0, 0, 0, 5, 2 },

{ 3, 0, 0, 6, 0, 6, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 6, 0, 0, 5 },

{ 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0 },

{ 0, 0, 0, 6, 0, 6, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 6, 0, 0, 0 },

{ 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0 },

{ 5, 0, 0, 6, 0, 6, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 6, 0, 0, 3 },

{ 2, 5, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 3, 5, 0, 0, 0, 3, 2 },

{ 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 0, 0, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2 },

{ 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 0, 0, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2 },

}

If we make some associations for example 0 to the sand terrain, 2 to the green mountain, 3 anti diagonal green mountain, 5 diagonal mountain, 6 green rock, 7 dungeon hole and drawn in right places we have the map as imaged by the original designers. If you look enough you can even see the map inside those numbers (like an ascii art).

What is important to note is the player will never be between two zones as we imaged in figure 5 by hypothetically putting the player where the blue mark is

The game design and programming choices regarding The Legend of Zelda were made concerned with the hardware of that time, but lets instead imagine that we could walk throught the entire game map without any load.

There are two solutions

-

Load the whole map in memory, in this case is around 22528 tiles, that is too much to fit the memory of old NES (2K internal ram).

-

Load as it moves, as the character moves in a direction drops the data outside and loads new information.

The second solution was used in games launched later, Zelda 2: The adventure of Link used that already.

Even nowdays, many games take a mix of the two approaches where a larger than screen map is fully loaded into the memory but only a portion of it is really drawn on screen, that area is controlled by a camera position. When a player reaches the boundaries of this area, a load screen is called, all map information is drop from memory and a new map is loaded.

This approach makes things simpler since the programmer do not need to take care about objects dinamically getting in and out of memory.

We will try to take an approach more general but lets start do define some keywords, concepts and ideas.

THE Grid world

First things first, lets create our fictional game world and call it WORLD, everytime i use the bold captilized word WORLD I will be making reference to the definition that we will discuss now.

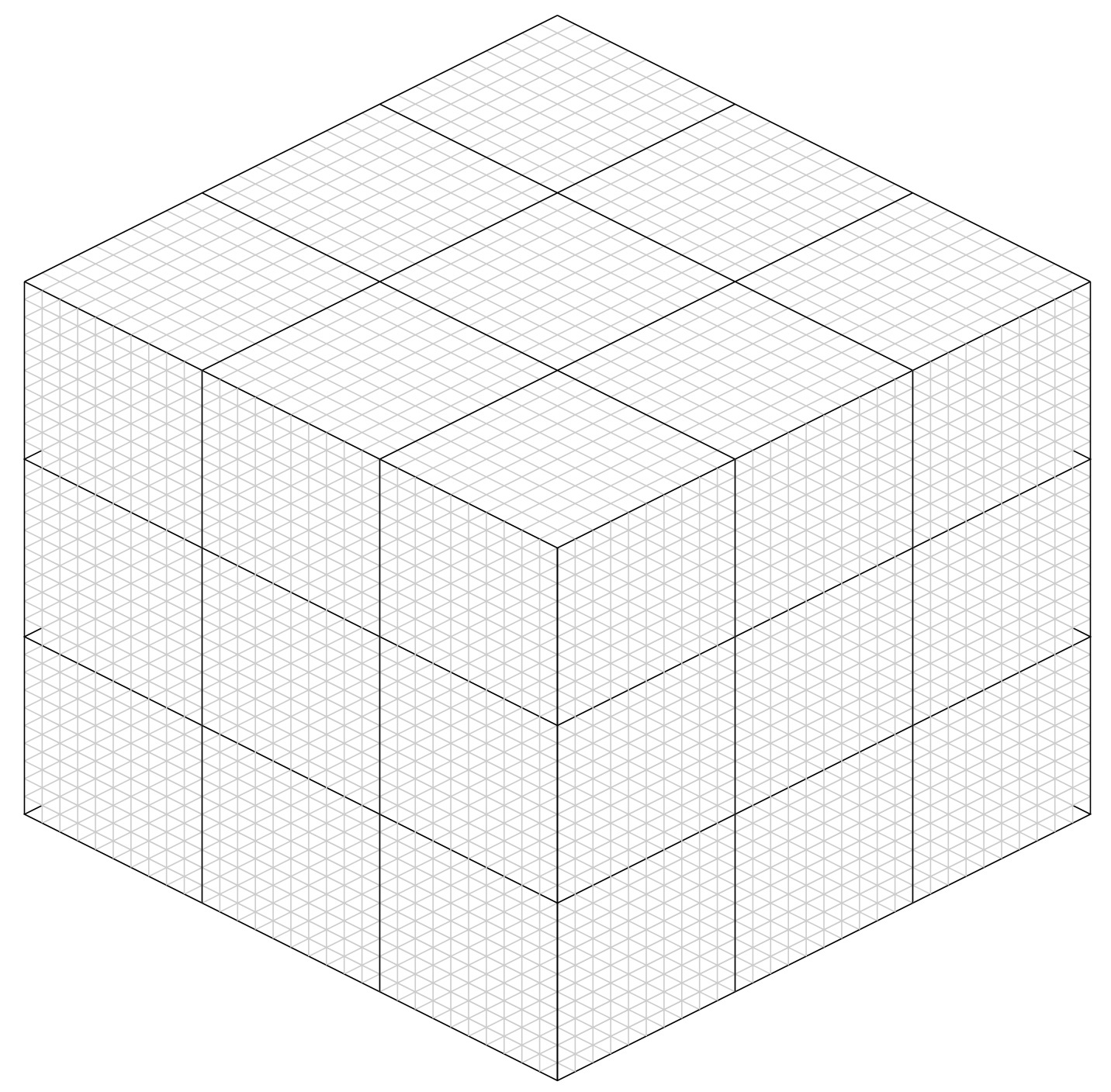

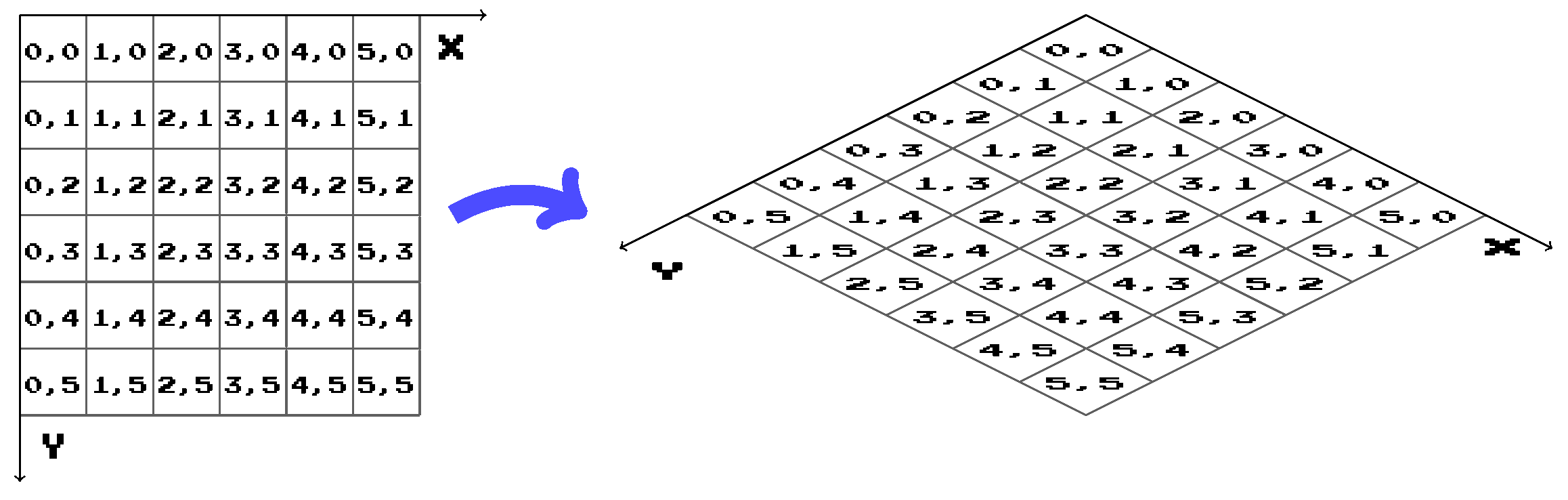

By my own limitations and choices the game world is a regular homogeneous tiled gameworld, it means I will discretize every location in world by a single element in a multi dimensional array, much similar to the way of Zelda’s approach, but there are two important differences.

First, the game world has infinite size, at least is very large, so large that could not fit in memory of the best computer nowdays.

Second, is a tridimensional world, at least for matter. Therefore the grid also expands above the plane, we can describe it as a grid on top of other grid, on top of other grid and goes on and on.

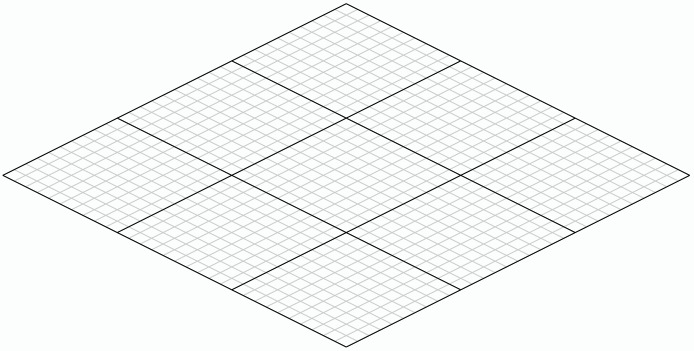

For camparison while games like Zelda draw over a 2D grid as shown in figure 7,

We can think of the WORLD as a stack of 2D grids as shown on figure 8,

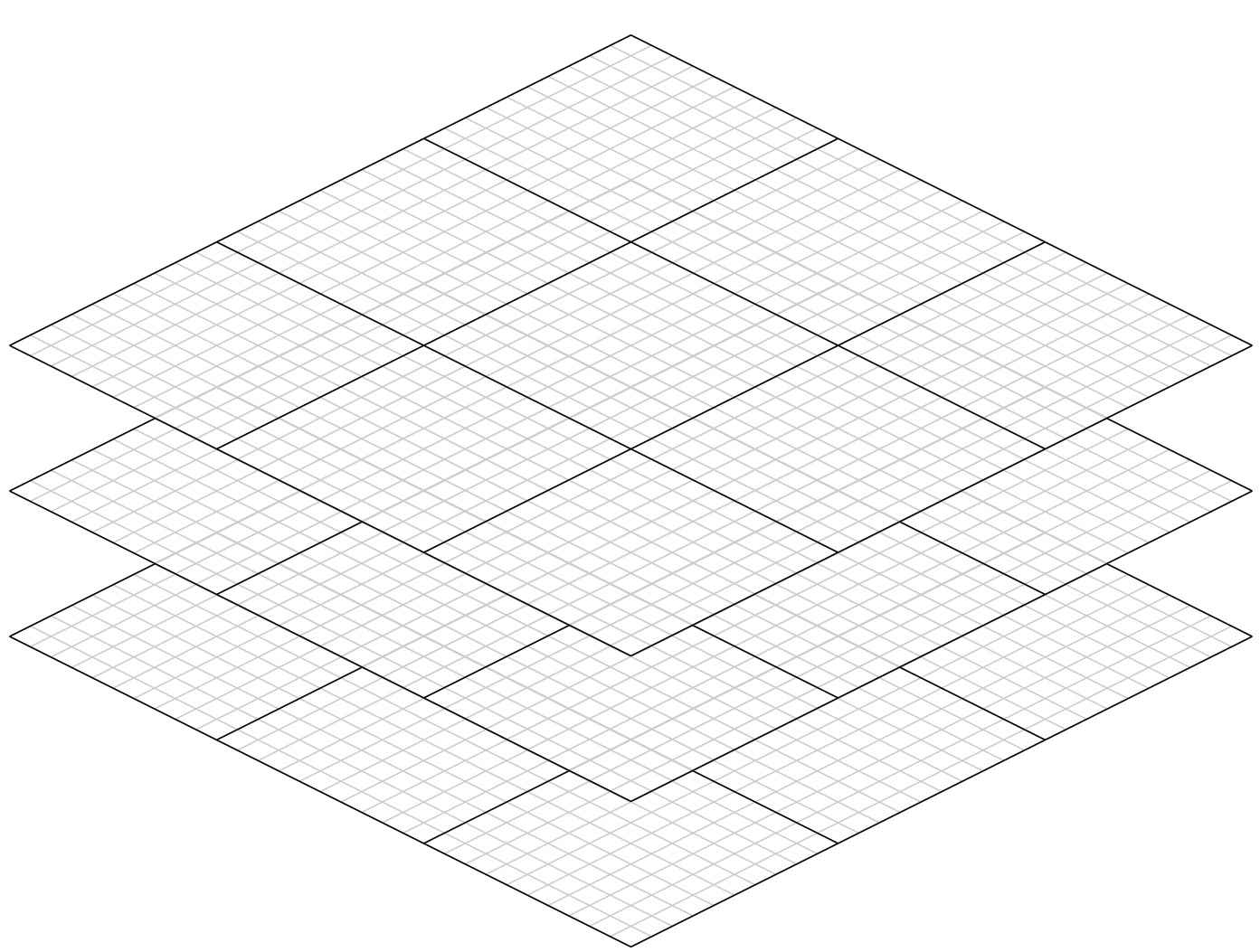

But lets not limit ourselves to 3 grids, lets supose we pack 30 grids one over another as shown in figure 9.

In the 3D Grid the things get even bigger, and very fast since every new layer on top of a plane is alike a whole new map of equal size.

For now we can imagine that the WORLD is like the figure 9 but instead a grid of size 30x30x30 we have a grid of size 100.000 x 100.000 x 1.000, isn’t easiliy drawable and that is just to materialize our idea, the core idea is infinity, But lets keep going.

A bonding window

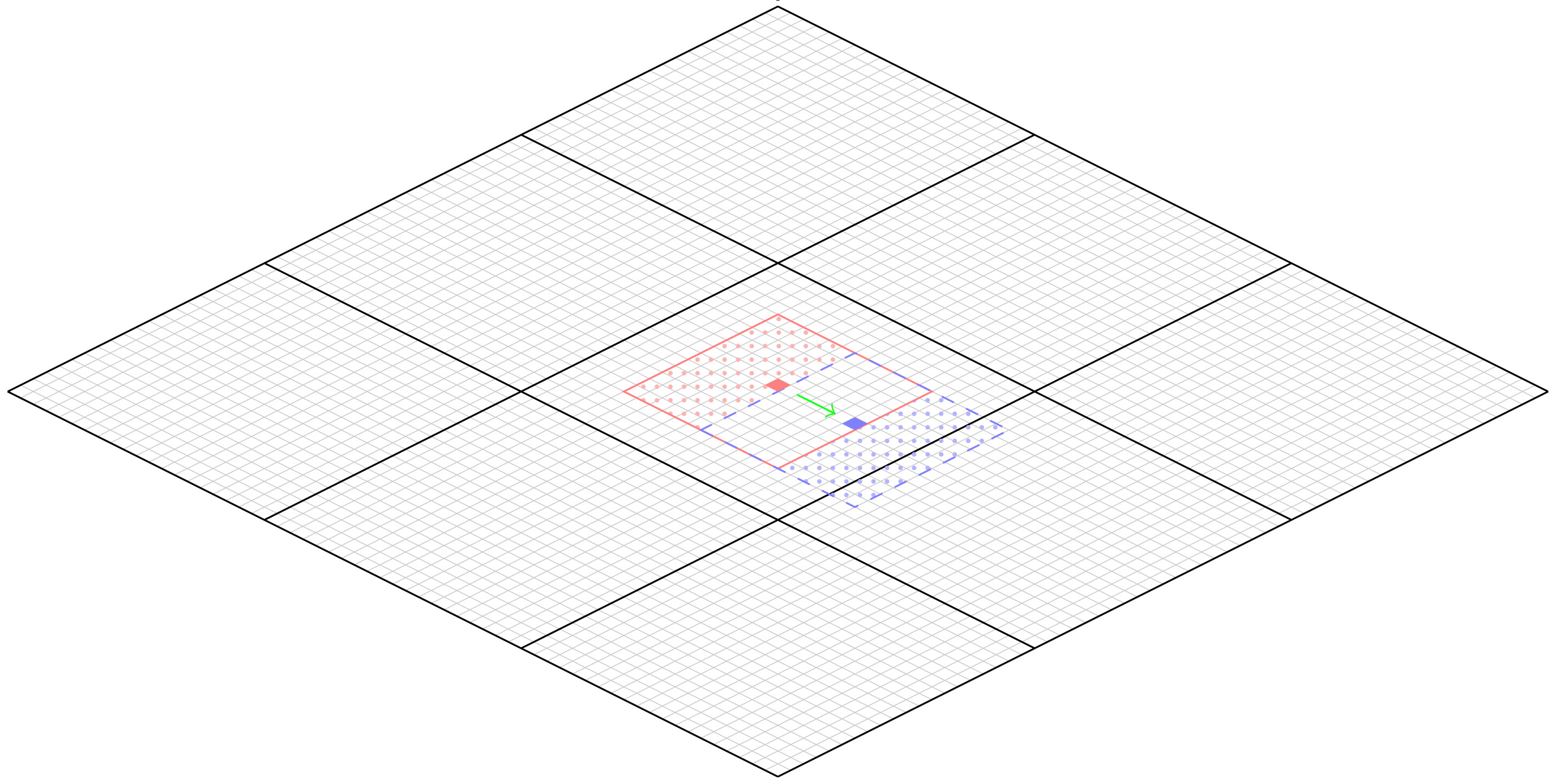

Lets go back to our 2D representation (it’s easier to draw and notice details), take a look af figure 10. The red filled square is the original player location in the game world grid (the exact coordinates do not matter), the red box around its all content in memory. There is no need to bring all data to memory just the data around a smart radius (in this case was 12 squares), do not care right now for the dots, just look to the whole red area (that also includes the dots, we will discuss them later).

When the player moves to another location, now represented by the blue square (green arrow shows the movement), the new bounding window is the one represented by the dashed blue area (including the area with the blue dots). But notice now, that the area with the red dots are outside of window and therefore need to be removed from memory (for sake economy), and the blue dotted area (as you can figure out), is the information that NEEDs to be read into the memory.

It’s very important to notice that there was no need to read the whole area around the character, just the new content. How that content is organized (is matter to another article).

By doing that, we can keep the memory usage under control, no matter the size of our map, in memory there is only a fixed ammount of grids.

The bounding window is often related to the player view area plus some area surrounding it, to make movement smooth (we will discuss the steps for that in another article).

But, another issue cames in, if grid is too big, will be hard to address all the content also, the I/O will be huge since we will keep reading areas on disk that can be too far apart. We will try to mitigate that slicing our data.

Slicing the grid

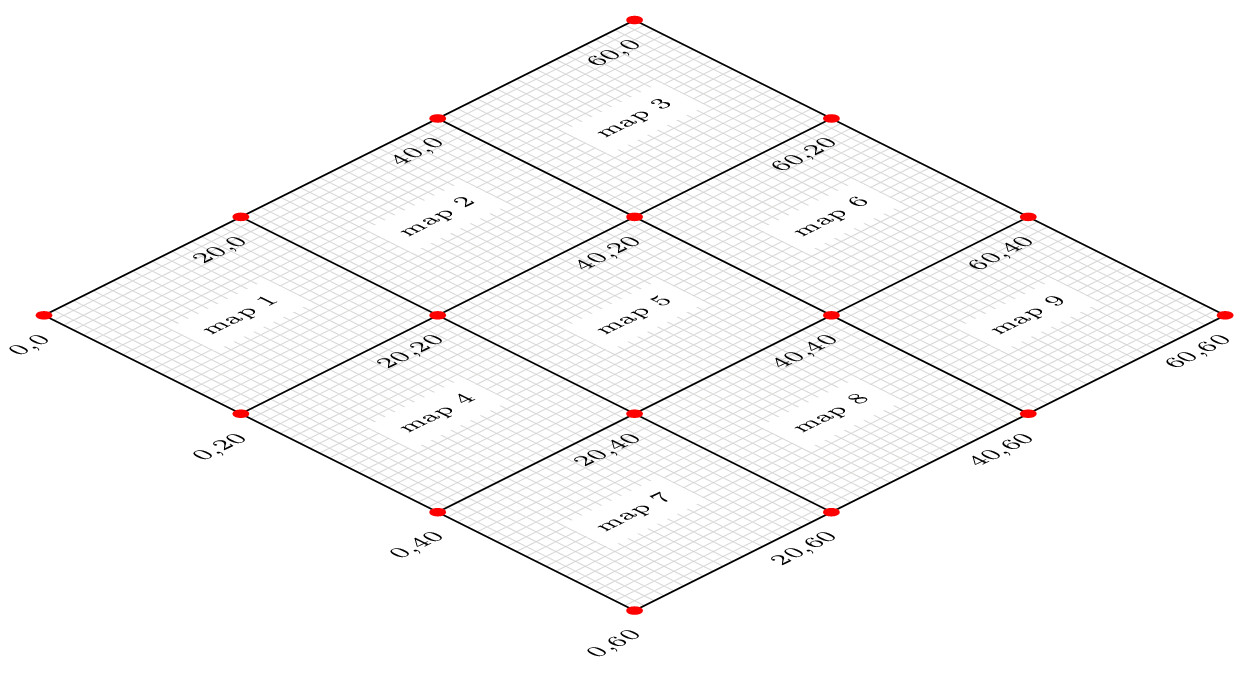

As you could probably noticed, in our grids we have drawn some light grey boundaries and some black boundaries. We can think of the grey boundaries as tiles inside a map and the black boundaries as limits of a chunk of map that is stored in a separated file, the exact amount of tiles per map isn’t important.

Note that the WORLD is the collections of all map files, glued one aside of the other (how this glue is done, we will discuss in another moment).

One thing that is very important is the number os tiles per map file, is finite and well know. We can fix, for example 1000 x 1000 tiles per map. (in figure we show just a few tiles because draw 1000 lines isn’t possible), therefore the size of each file is very manageable, it can be probably load completely in the memory in a good enough machine.

And one amazing thing, no matter where the player is, it never touches more than 4 map files per time. One restriction here is that the bounding window is never bigger than the smallest map file. Looking the numbers, it will never be, since the bounding window is associated with the player view screen, that barely goes larger than 30 x 30 and we can preload some neighboor areas to make things smoother, that goes like 50 x 50 since we can consider that the player never moves faster than 10 tiles per second, we can always adapt the surround area just by knowing the fastest speed that any player can move in a second and preloading the double ammount of it. In the other hand a map file should have at least 1000 x 1000 tiles in a compressed format.

Another important aspect is the coordinate system. There is no local coordinate system, the coordinates are absolute based in the whole map, being (0,0) a map orgin, maps connected in boundaries have their coordinates summed as we can see in figure 11.

Getting to the border

But what happens when the player is very near of a border and it needs data that is outside the file map he is right now? This should not be an issue since as we can see from figure 10, is impossible to the player be neighboor of more than 4 maps, therefore in the worst case you will have part of 4 different files loaded on memory and the I/O seeks while not optimal are upper bounded (we will think of optimizations later).

Infinity

With that concepts is possible to have infinite maps, limited only by the disk space (that is the cheapest) of the limits, if we take in account some compression methods as the Blosc Library we can have file acess faster than memcpy with sizes compressed to a ratio of 10:1.

Going 3D

The same concepts of a 2D grid can be applied to the 3D grid of the WORLD, the single difference is that instead a maximum of 4 files in boundaries at same time, we have 8, 4 above and 4 below if you’re in a vertex. Besides that all concepts apply. In fact, we can think of the 2D case as the 3D case where the z grid size is always 1.

The WORLD tile

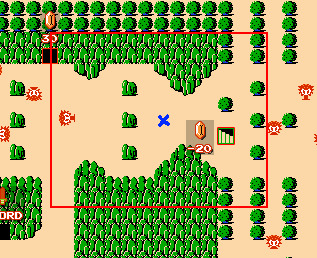

Once we are set in how the WORLD is mapped we need to know what is stored in each one of those tiny blocks called tiles. Lets go back to our Zelda game (another location just for fun) in our figure 12. Each game “square” has e direct equivalence with a matrix position and value.

Let’s say for sake of example that the following table shows the tiles and its equivalence with a number

| Number | Tile |

|---|---|

| 1 |  |

| 11 |  |

| 13 |  |

| 14 |  |

| 15 |  |

| 16 |  |

If we map our world starting in top-left position (as we can see in the left side on figure 13), and moving the coordinate to left and th coordinate down, we can say that position on the matrix representing this map contains the number . And was not totaly by coincidence I have choosen numbers below 10 to walkable tiles, and values above 10 to non walkable tiles. Of course this additional information could be stored somewhere else, for example another associated map containing only and where is walkable path, and is non walkable path, it is also a valid approach, this map is called collision map and is a fast way to know if the player can walk or not for a region since is often small (1 bit only) per tile. A third approach is pack the collision map inside the regular map, for example the first/last bit is the collision, for a 8 bit system it turns numbers above or equal 127 collidable, and numbers below 126 non collidable.

But more complicated games could have more information in a single tile

- The tile structure and placement

The datastructure

typedef struct vt_map_t {

// Map origin regarding the **WORLD**

int32_t x0;

int32_t y0;

int32_t z0;

// Grid size of this map in (x,y,z) directions

// No single map is bigger than 65535 in any

// direction, if it is, you should split it.

int16_t nx;

int16_t ny;

int16_t nz;

// Size of tile in (x,y,z) directions

int16_t dx;

int16_t dy;

int16_t dz;

// Map unique ID (UID)

int16_t uid;

// Map unique name (can be accessed by name too)

// 256 - 2 for better packing

char name[254];

// Tile data

vt_tile_t *tile;

} vt_map_t;

typedef struct vt_tile_t {

/* vt_tile_t: represents the layers over a tile

*

* size: 16bytes (64bit arch)

* size: 12bytes (32bit arch)

*/

// tileID to associate to, often the tileID is related

// to an Atlas/Spritesheet block

int16_t id;

// The layer offset (x,y,z) is used to position the

// layer content sligtly shifted from central location,

// for example if you want to move the floor up

// or a wall hanging light.

int16_t x_offset;

int16_t y_offset;

int8_t z_offset;

// The layer status.

// Right now just 8 bit flags exits, we can extend

// if needed some ideas:

// WALKABLE 0x01 (you cannot move down this layer)

// SWIMABLE 0x02 (you can move down and up if you know how to swim)

// FLYABLE 0x04 (you will move down if do not have fly ability)

// JUMPABLE 0x08 (you can cross jumping but not walking ??? )

// TRANSFORMABLE 0x10 (you can change, grass can be cut, hidden walls opened)

// ... 0x20

// 0x40

// 0x80

char status[1];

// Points to another layer over the actual tile

// that is useful if you need to add more objects

// or textures over the same tile, here the offset

// comes handy to add some "noise" in the placement

// of common materials.

vt_tile_t *next;

} vt_tile_t;

Another datastructure idea

typedef struct vt_map_t {

// Map origin regarding the **WORLD**

int32_t x0;

int32_t y0;

int32_t z0;

// Grid size of this map in (x,y,z) directions

// No single map is bigger than 65535 in any

// direction, if it is, you should split it.

int16_t nx;

int16_t ny;

int16_t nz;

// Size of tile in (x,y,z) directions

int16_t dx;

int16_t dy;

int16_t dz;

// Map unique ID (UID)

int16_t uid;

// Map unique name (can be accessed by name too)

// 256 - 2 for better packing

char name[254];

// Tile data 190MB uncompressed

vt_tile_t tile[500][500][50];

} vt_map_t;

This idea will take around 1.5G per map uncompressed, is too much if we think we can be touching maximum of 8 maps. Of course read all the 8 maps in memory isn’t the right approach.

Reducing to the half of all 3 coordinates (500x500x50), it reduces to 190MBs uncompressed per file, that is pretty feasible even in low cost machines or mobiles.

Mayube checking the compression ratio of some sample maps (with 1000 and 500 in size) using blosc we can find a good solution.

Also think about the offset idea in tile, I think that is a good idea, even z_offset can be used to create smooth terrain changes, maybe will drop the x, y offset and let only the z offset for small terrain vertical changes.

Also, maybe pack the tile and prop values into a small pack as defined in Bit packing and The lost art of C structure packing.

Results

Need to test stuff not just chitchat and add some data

Conclusions

Here some conclusions

Questions

-

How to optimize the data structure for cache locality?

-

How to serialize the data on disk since tiles are unknown and prop too?

-

I can fix the number of props over a tile for a small qantity for example 8, I think that isn’t so limiting, but it will create a waste of memory since IMHO most of time (like 90%) it will have 0 or 1 prop over a tile.

-

Is there better ways to organize data to achieve the same design results?

-

For open spaces will not be to “draw” too much emptyness?

-

How make props stay near the tile without too much memory expanse?